Thank you for visiting my business writing blog. The current topic is sentence diagrams. If you’ve never done it, please start with “Diagramming Tutorial No. 1” and work your way through. Diagramming is the best way to learn grammar, so stick with it.

Thank you for visiting my business writing blog. The current topic is sentence diagrams. If you’ve never done it, please start with “Diagramming Tutorial No. 1” and work your way through. Diagramming is the best way to learn grammar, so stick with it.

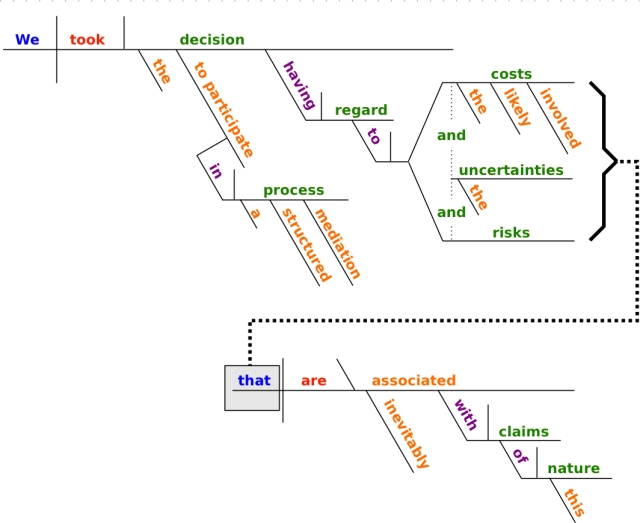

The sample sentence for this tutorial comes from a friend’s CV cover letter. It stars everybody’s favourite subject — ourselves. Or does it? Who or what is the grammatical subject of this sentence?

My track record in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT) has helped improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

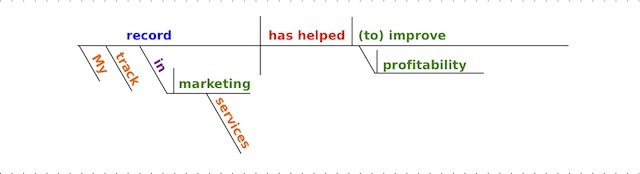

I highlight the subjects of sentences in blue:

My track record in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT) has helped improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

The verb is highlighted in red:

My track record in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT) has helped improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

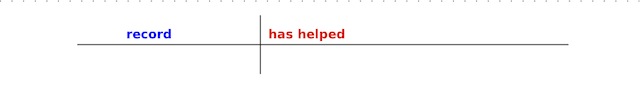

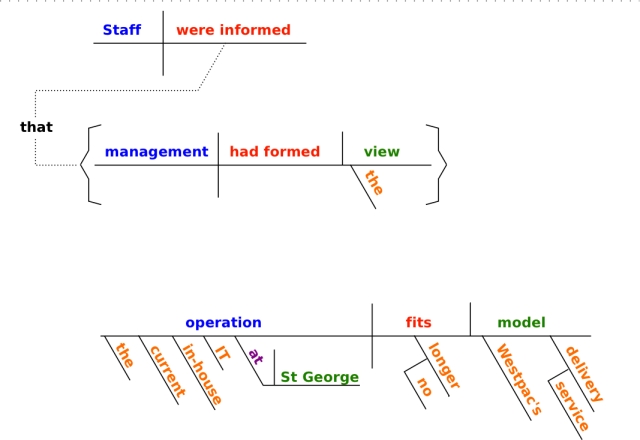

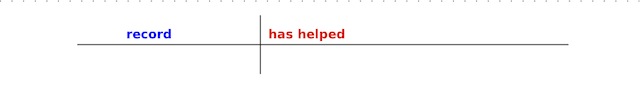

Draw your story line, and write the subject and verb either side of the dividing line.

Does the verb have an object? In other words, what was helped? That’s not such an easy question. The story is easy enough to understand; my friend helped corporations improve their profitability. But the object of has helped seems to be ‘(to) improve’. I highlight objects in green.

My track record in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT) has helped (to) improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

Were did I get that ‘(to)’ in parentheses? It’s what I call a virtual word — also known as an ‘understood’ word. These are neither written nor spoken but are required to fill a slot in the grammatical structure. They are understood to be there, even when they are not there. Diagram virtual words in parentheses.

In this case (to) is required to make improve into an infinitive. You learned about infinitives in Diagramming Tutorial No. 2. They’re the basic form of all verbs, but they are used as other parts of speech. In this sentence the infinitive to improve is used as a noun.

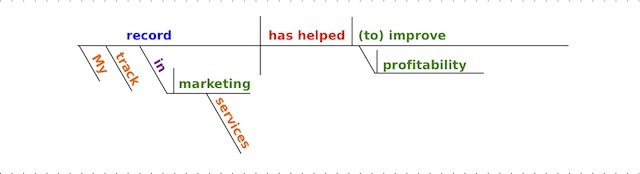

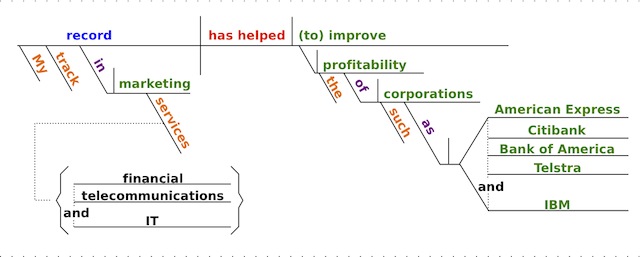

Remember how to diagram objects: Draw a vertical line down to the story line, but not through it. Put the object to the right of that line. Here’s how your drawing should look:

Infinitives can take objects, just as prepositions do. In this case the object of the infinitive is profitability. Highlight objects in green. You’ll notice that we now have an object of an object.

My track record in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT) has helped (to) improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

Diagramming the object of an infinitive used as a noun is tricky. Putting it up on the line would confuse the diagram, because we have an object of an object.

The authorities want you to put the entire infinitive phrase on a little stand, but that’s too complicated as a picture. (Official method here — http://grammar.ccc.commnet.edu/grammar/diagrams2/diagrams_frames.htm)

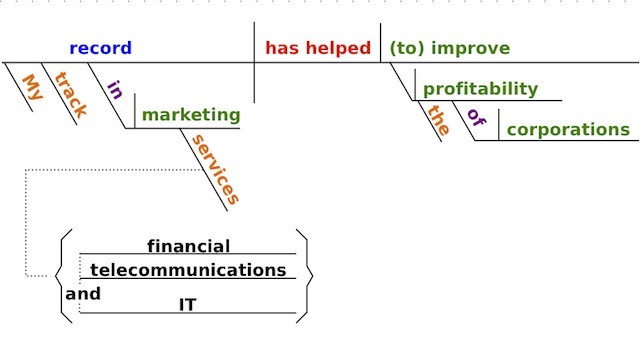

I put the object below, on a dog-leg line. It looks just like a prepositional phrase, but without the preposition. Here’s the diagram:

That’s the story line completed. The story line gives you the bare, grammatical bones of a sentence. This one says, ‘record has helped (to) improve profitability’.

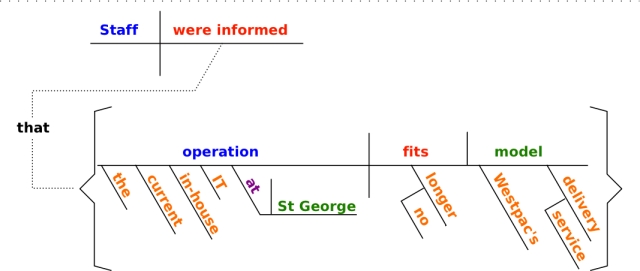

The next job is to identify modifiers of the story-line words. Modifiers answer questions we might ask about the words they modify.

For instance, we might ask ‘WHOSE record?’ – ‘My record’. Like all possessives, ‘My’ is a modifier. Then we might wonder ‘WHAT KIND of record?’ – ‘track record’. I highlight modifiers in orange.

My track record in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT) has helped improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

Diagram modifiers on slanted lines below the words they modify:

Another answer to‘WHAT KIND of record?’ is the prepositional phrase – in services marketing. I highlight prepositions in generic purple. The objects are green – same as objects of verbs and infinitives. Modifiers, if any, are orange.

My track record in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT) has helped improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

You learned to diagram prepositional phrases in Tutorials 1 & 2. Put the preposition on a slanted line. Put its object on a horizontal line. Put the modifier on a slanted line below the object.

Here’s how your diagram should look:

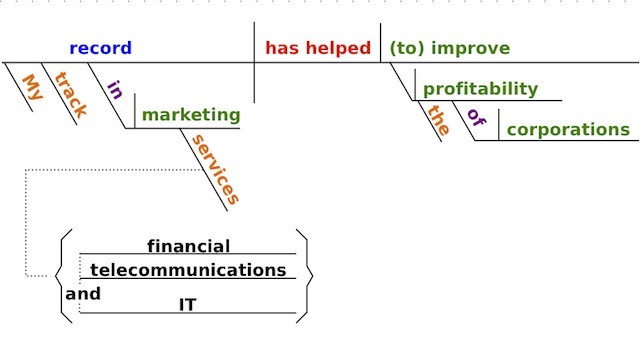

What shall we do with the words in parentheses – (financial, telecommunications and IT)? You will be delighted to learn that even grammar geeks label this structure in Plain English. It is a parenthetical phrase. Parenthetical phrases give essentially repetitive information about the words to which they refer. You can remove them without upsetting the grammar, syntax or meaning of the sentence.

Parenthetical phrases should be placed immediately after the word to which they refer – in this case, services. But my friend placed it after marketing, which is slightly confusing. Ironically, this is yet more proof of the power of diagramming. When something is difficult to diagram, that’s a clue that it needs to be edited

I diagram parenthetical phrases by putting them in brackets, as though they were clauses. Brackets are graphically the same as parentheses.

As you did when diagramming clauses in Tutorials 2 & 4, run a dotted line from the point of one bracket to the word to which the phrase refers. It should look like this:

Incidentally, don’t get hung up on positioning things like parenthetical phrases. I put this one where it is to keep the diagram as large as possible within the column width of this blog template. When you’re drawing them by hand – on a BIG piece of paper, like A3 – put them in the most logical place, or wherever you have room.

Incidentally, don’t get hung up on positioning things like parenthetical phrases. I put this one where it is to keep the diagram as large as possible within the column width of this blog template. When you’re drawing them by hand – on a BIG piece of paper, like A3 – put them in the most logical place, or wherever you have room.

For example, here’s a fragment of what would be a much larger diagram, showing the parenthetical phrase directly to the left of services.

Finally, identify any modifiers of the object of the infinitive, profitability. We might ask the question, ‘WHICH profitability?’ First answer: ‘THE profitability.’

The second answer to ‘WHICH profitability?’ is given by another prepositional phrase – of … corporations.

My track record in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT) has helped improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

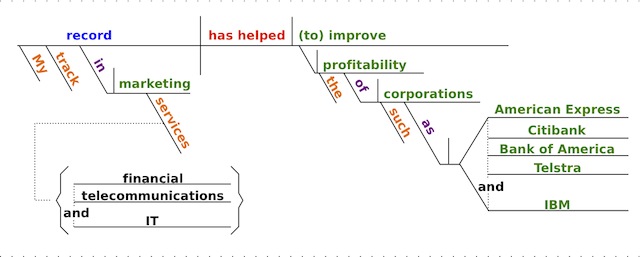

Let’s diagram just that much:

Now take a deep breath, because it’s going to get messy. First, look at the two words, such … as. Technically they form a compound preposition or, even more arcanely, a phrasal preposition. And while I understand the reasons for these clumsy labels, I’m not convinced they’re necessary.

I think the argument for calling ‘such as’ a compound preposition starts with the assumption that the two words are placed together. So, is there any grammatical difference between these two phrases?

1. ‘… of such corporations as American Express…’

2. ‘… of corporations such as American Express…’

You can see that there is no difference. This leads me to label ‘such’ a modifier and ‘as’ a preposition. I highlight modifiers in orange, prepositions in generic purple, and objects in green:

My track record in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT) has helped improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

So the diagram looks like this:

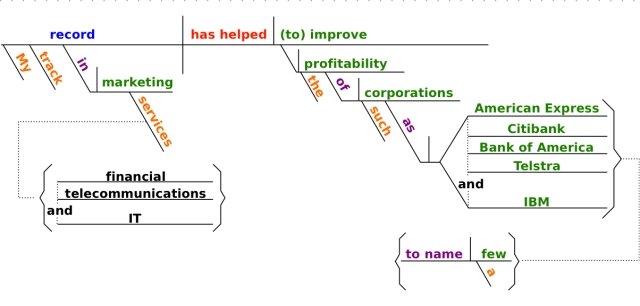

Now all that’s left is the infinitive phrase, to name a few. It seems to be commenting on the list of corporations, but it doesn’t really modify them in the sense of answering logical questions. In fact it’s another parenthetical phrase, but without the parentheses. Diagram it in brackets, like the other parenthetical phrase. And use a single bracket to indicate that it refers to all of the corporations listed.

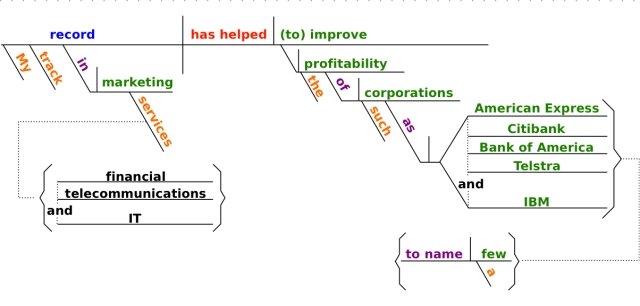

Now all that’s left is the infinitive phrase, to name a few. It seems to be commenting on the list of corporations, but it doesn’t really modify them in the sense of answering logical questions. In fact it’s another parenthetical phrase, but without the parentheses. Diagram it in brackets, like the other parenthetical phrase. And use a single bracket to indicate that it refers to all of the corporations listed.Your finished diagram should look much like this:

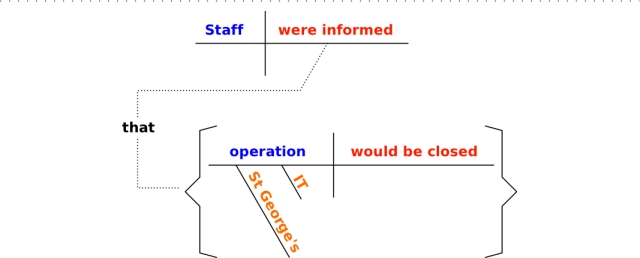

Now you probably spotted the fundamental flaw in this sentence when you drew the basic story line diagram. It has the wrong subject. My friend’s record didn’t help those corporations’ profitability; she did.

So let’s fix that first, then look at the rest of the sentence. The new subject is I and the verb is helped.

I helped improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

Now where do we put the left-overs: My track record in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT)? I would suggest an introductory phrase, like this:

Working in services marketing (financial, telecommunications and IT), I helped improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM to name a few.

The participle, working, modifies the subject. The prepositional phrase modifies working. With the Stage 1 Fix, the sentence is diagrammed like this:

Now we can clean up the rest of it. Remember you learned to identify parenthetical phrases by removing them from the sentence to see if it was damaged? That’s your clue. With the commentary removed, we’re left with this:

Working in services marketing, I helped improve the profitability of such corporations as American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM.

Here’s the diagram:

Note that both parenthetical phrases were redundant:

- ‘financial, telecommunications and IT’ — These merely gave the categories of the corporations actually listed. They added nothing.

- ‘to name a few’ –My friend was trying to indicate that she had also worked at other big-league outfits. But if they were truly in the same league, she would have listed them as well. The comment added nothing of value.

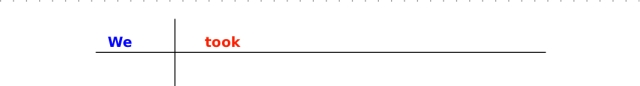

But this means we could also get rid of ‘such … as’, for the same reason.

And if we’re serious, we could do away with the entire introductory phrase. Other parts of the cover letter – not to mention her CV as well – made it clear that she worked in marketing. The corporations listed are all service marketers. Therefore the intro – ‘Working in services marketing’ – is not really necessary.

We’re left with a straightforward statement of competence and experience:

I helped improve profitability at American Express, Citibank, Bank of America, Telstra and IBM.

The diagram is now much cleaner:

Thank you for sticking with me on this.